Table of Contents

- How much is your time worth?

- What is the cost/value of your work?

- Calculating the market value of your time.

- How to know your worth.

- How to prove to your boss the value of your time.

- How to evaluate time spent closing a lead.

- The value of meeting time.

- How do you calculate the value of the meeting time as a whole?

- How to prove the success of a meeting.

- How to show your value on a project.

- How your Calendar plays into the value of time.

- Money vs time.

What do The Pope, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, and the barista at your local Starbucks, and you have in common? You all have 24 hours in a day. You all have seven days in a week, twelve months in a year, and 365 days in a year. No one gets more time or more days — time is divided exactly evenly for everyone. The value of time might not be the same for every person — but we all have the same amount.

Time is the great equalizer. Whether you’re born into the world’s wealthiest family, have risen to the top of a global conglomerate, or spend your working hours heating milk and pouring it into plastic containers, your day will have exactly the same amount of time.

What makes the difference between many people is their perception of the value of time.

In 2020, every hour has a price. Work and life are moving faster than ever. That’s true whether you’re an entrepreneur, a freelancer, or an employee. Every hour of work uses knowledge, skill, and talent to turn minutes into money. How much money comes out of the other end of those hours depends on the knowledge, skill, and talent you possess.

What comes out at the other end of those daylight hours also depends on how efficiently you use that knowledge, skill, and talent. The more attention you pay to those passing hours and the clearer your understanding of the value of your time, the more likely you will be to treasure it. You’ll waste less time and earn more money.

In this guide, we’re going to look at ways to measure the financial value of time. We’ll look at the value of your work and the cost of your hours.

We’re also going to explain how to prove that you’re worth more than you are currently earning. We’ll help you to demand an hourly rate that’s higher than you’re currently charging.

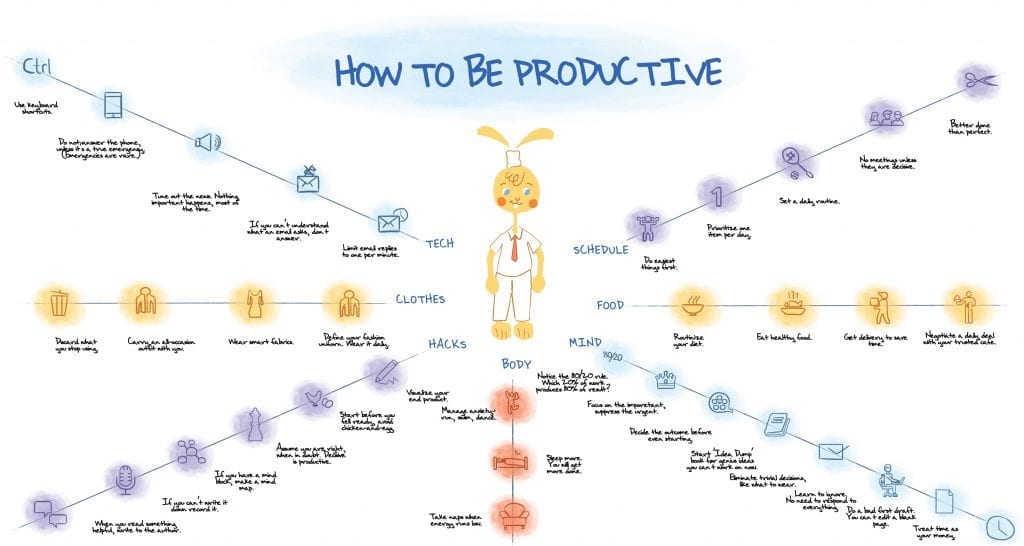

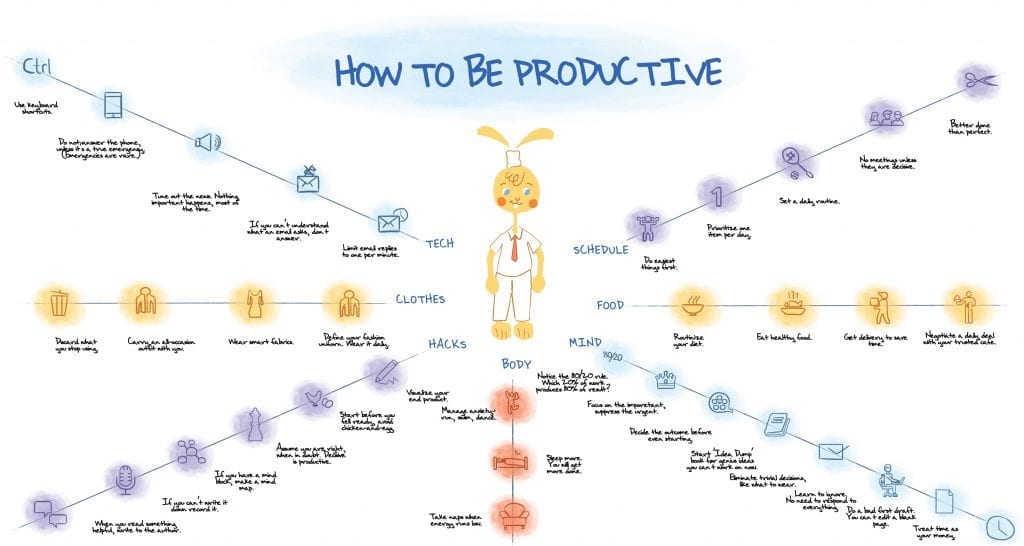

We’ll also explore some of the biggest time-sucks in the workplace: the hours spent trying to close a deal; especially the hours lost in meetings. We will offer some suggestions for cutting that lost time and for maximizing productivity.

We’ll explain how to make the most of what may be your most important productivity tool in 2020: your calendar.

By tracking your hours and measuring the value of your work time — your free time — and your personal time — you’ll always know exactly how much income your time is worth. You can then make the most of your working hours while enjoying the free time and the personal time that surround them.

Let’s start by calculating the financial value of your time. Financial value is going to require a bit of math.

How much is your time worth?

In theory, calculating how much your time is worth should be reasonably straightforward. If you earn $50,000 a year, for example, you’re making $4,167 every month. There are four weeks in a month, which means that each week is worth $1041.75. There are five days a week, so each day is worth $208.35.

Because there are eight hours in a workday, each hour is worth $26.04. In practice, that sounds good. But in reality, it’s not quite as simple as that.

Let’s try another calculation. The typical workday lasts eight hours. There are five days a week, so each week contains 40 hours of work. There are 52 weeks in a year, so each year contains 2,080 work hours. Divide $50,000 into 2,080 hours and you get $24.04. This amount is a couple of dollars less each hour than the first method.

The problem, of course, is that there aren’t precisely four weeks every month, and even the number of days in a year changes every four years. The calculations we’ve described here will give you a rough idea of the financial value of an hour, but it won’t deliver an accurate accounting for you.

For large organizations, the difference in accounting matters. The Federal Government, for example, employs about two million people.

Adding a couple of dollars an hour to all of those employees’ annual pay would cost more than $8 billion. That’s one reason the government prefers to use the second method to calculate the hourly wage of federal employees. It’s also more accurate, and the government uses a variant of that method.

Until 1984, the government would calculate an employee’s hourly rate by dividing the annual salary by 2,080 hours. It then rounded the figure to the nearest cent. But those 2,080 hours still only represented exactly 52 weeks or 364 days. A calendar year contains either 365 or 366 days.

If the federal government used 2,080 hours to calculate an hourly rate, its employees would have to work at least one day a year for no pay. The General Accounting Office (GAO) came to the rescue. In 1981, the GAO study revealed that over in the 28 years it takes for a calendar to repeat itself:

- Four years will contain 262 workdays or 2,096 work hours.

- Seventeen years will contain 261 workdays or 2,088 work hours.

- Just seven years will have 260 workdays or 2,080 hours.

The GAO then calculated (2,096 hours for four years) + (2,088 hours for 17 years) + (2,080 hours for seven years) over a 28 year period = 2,087.143 hours. So the average number of work hours each year is actually about 2,087 hours. The converted figure for the hourly value of a worker earning $50,000 is $23.96.

What is the cost/value of your work?

However, the value of an hour charged to an employer isn’t quite the same as the hourly value of work. Employees are also entitled to vacation time and holiday time. That’s the amount of time they’re paid for without producing output. It increases the value of the time that they are working.

How much time off an employee receives can vary. France, famously, gives its workers 25 days of paid vacation every year. Add on another eleven national holidays, and people in France get paid for not working on 36 days each year. That’s 288 hours, making their work year just 1,799 hours.

The United States has no statutory paid vacation time — or paid public holidays. In practice though, staff usually receive eight paid public holidays every year and ten vacation days, with that number rising with years of service.

Other countries love to bash the U.S. about working around the clock and never taking off work — but consider the two-week paid vacation, and the typically paid holidays provided by the employers in the U.S.

Listed here are the eight most typical “paid holidays” that employers will allow employees to take off during the year; these days off also provide added compensation to their employees:

- New Year’s Day

- Easter

- Memorial Day

- Independence Day

- Labor Day

- Thanksgiving Day

- The Friday after Thanksgiving

- Christmas Day

In addition to the commonly paid holidays, many employers will consider the U.S. federal holidays as paid time off for their employees. These federal employee holidays include:

- New Year’s Eve

- President’s Day

- Martin Luther King, Jr. Birthday

- Veterans’ Day

- Christmas Eve

Calculations for a typical U.S. employee.

If you consider a typical U.S. employee as an example, you’ll need to deduct eighteen days, or 144 hours, from 2,087. A worker who earns $50,000 will have made that money in 1,943 hours of work. So, the value of an employees hour of work is actually, $25.73.

If you also receive the extra five U.S. holidays from your employer, you’ll deduct twenty-three days, or 184 hours, from 2,087. You’ll be earning your $50,000 in 1,903 hours of work; the value of an employees hour of work, in this case, is, $26.27.

To calculate the value of your time, you make the following calculation:

(Annual Income) divided into 1,903 hours = the actual value of each hour of your work.

This calculation tells you the amount of money you generate each hour. It doesn’t tell you the amount that you could generate in an hour. Nor does it tell you the amount that you should generate in an hour.

Earn what you can, not what you need.

Imagine that a freelance graphic designer was trying to work out their hourly rates. They estimate that in their city, they’d need $65,000 a year to live comfortably. That amount would give them enough to pay the rent, buy food, run a vehicle, buy their clothing, pay their health care deductibles, have a social life.

The freelancer would still be able to squirrel away a little cash each month for vacations and hobbies.

That annual income works out to be $33.45 every hour. When the freelancer needs to give a quote for a job that they estimate will take a hundred hours, they can charge $3,345 knowing that for those hours, they’d be earning enough to live the lifestyle that suits them.

This estimate would be an easy calculation. The freelancers’ competitors might be charging more, but they might have higher expenses. If the designer doesn’t need that extra money now, they could swap some income that they don’t need for the ability to land work whenever they want by undercutting other designers.

But lives change. Expenses rise. Kids come along and need child care, camp fees, and a college fund.

That graphic designer might soon find themselves needing an extra $15,000 a year to maintain their standard of living, an additional $7.72 an hour. Now they have to tell their clients that they’re charging more because of the rise in their cost of living. It seems to be a life fact — expenses get more expensive each year.

However, it’s quite unlikely that clients used to paying a bargain rate are going to take kindly to suddenly having to pay substantially more. Whether you’re an employee or a freelancer, you should always be charging an amount based not on what you need but on the market value of your time.

Calculating the market value of your time.

It’s fairly simple to calculate the actual hourly value of the work you do. It’s much harder to calculate the market value of the work that you do.

The market value of work is set, not by how much you need to live on, or how well you’d like to live. It’s set by the supply of the skill you offer — a factor of its difficulty — and by the demand for that skill.

Hedge fund managers, for example, is a harder skill to acquire than pediatric nursing. While the work of a pediatric nurse has a high social value — hedge fund managers can charge much more for each hour of work that they perform.

Understanding market value.

The first step to understanding the market value of the work you perform is to check the dollar amount that competitors are charging in your area. If you’re looking for a job, you’ll soon find that the pay grade, or offer, falls into a somewhat limited range.

Employers will have already done their research, and they’ll know how much they should be paying for your services.

If you’re wondering how to set rates for your own business, though, you’ll need to look for firms that offer competing services. New companies often start at the bottom end of the market value scale to build a client base.

Larger, more experienced firms are often able to charge more because they have more to offer: a stronger reputation and cheaper additional services.

A graphic designer who earns $65,000 a year, for example, is making $33.45 an hour. But they’ll quickly find that not all that money will be profit. They’ll need to spend some money on advertising and client acquisition.

Servers cost money. They’ll need to buy expensive, professional software and pay their own taxes.

To earn $33.45 an hour — the freelancer might well have to charge three or four times that amount. As long as the client is willing to pay that amount, the fee is the real market value of the skill required to supply the demand.

It’s what a graphic designer could charge for an hour of their work.

How the value of your hours varies.

What a graphic design customer buys when they pay that hourly fee isn’t an hour of time. They don’t get an extra hour in their day for their money. What they get is what the graphic designer can produce in one hour.

What they can produce might be a page of a website, a logo, or a color consultation. It’s one hour of skilled work. The challenge for the graphic designer is that the amount of effort each job will entail delivering the best work will vary.

Having a different value placed on the work means that the value of their hour will vary too.

Parkinson’s Law states that work expands to fill the time available.

When deadlines are distant, and there’s little demand at the end of the job, workers tend to work more slowly. The closer they come to the end of the task, the more slowly they work.

Working more slowly lowers the value of their time. On the other hand, when deadlines are tight, and work is piling up, the focus is razor sharp and distractions are less tempting. Workers get more done in less time making the value of their time.

There’s a big difference between the value of the work you could produce in an hour, the value of the work you sometimes produce in an hour, and the value of the work you usually produce in an hour.

When you’re calculating the hourly value of your time, ignore what you could produce when the pressure is on. No one can work like that all the time without hitting burnout.

Ignore too, the minimum you’ll produce when there’s no pressure and you feel you have all the time in the world. Fortunately, those times are rare, too.

Measure your average output over a week or two. Compare that output with what competitors charge for a similar product to make sure your work rate is competitive.

If you’re working too slowly to charge what others are charging, put away the social media, turn off the distractions, and increase your productivity to bring up the value of your time.

How to know your worth.

The market will determine the value of your skills.

Your productivity will determine how much money those skills can generate in an hour. But the “value” of your work isn’t the same as its “worth.” Worth starts with value but it’s not limited to the financial benefits that you bring to a business. One aspect of worth is the degree to which the company depends on your efforts.

A company might charge a client $120 an hour for the services of its chief graphic designer. The amount charged represents the hourly value of the designer’s work.

A client may choose to remain with a particular business because they’ve grown used to working with that designer. They know that that designer understands their needs and can deliver work that they like.

In addition to the professional knowledge that someone brings to their work, they also bring institutional knowledge.

The employee brings an understanding of the kinds of clients that the company serves and the way they like to be served.

No one is irreplaceable. Some people may be harder to replace than others, but no set of skills is entirely unique. Even Apple survived the passing of Steve Jobs.

Tim Cook might not have the same set of skills as his predecessor but he has done a perfectly good job of leading the company since taking over. He was able to step into his former boss’s shoes.

Someone will always be available to step into the shoes of any other professional and deliver a similar set of skills. Experienced and competent employees can be found whether the skills being sought after are graphic design, coding, creating marketing campaigns, or painting walls.

What has less replaceability in a company is institutional knowledge. A new hire won’t know how the company works — and they won’t know the clients. Of course, the skillful knowledge and understanding of the inner workings of a business can be taught — and learned — but it takes time.

An employer will expect that any new hire will need at least a few weeks and more likely a few months to get used to the new business.

Realizing the time-suck a new hire needs to come up to speed might be is why new employees often have probation periods. It’s not just a time for the new hire’s manager to make sure that they really do have the skills they listed on their resumé.

It’s also a chance to make sure that the new hire can match the company culture and fit into the new workplace.

Until that new hire is as knowledgeable about the company and its clients as their predecessor, they’ll be less productive.

They’ll need more time to have processes explained, and their work may require more revision—not for quality but to match the particular needs of the client. That new hire period carries a cost, and it’s a cost that adds value to the skills that an established employee brings to the company.

A graphic designer might have a maximum value of $120 an hour to a company’s revenue. But in their first month of work, their value might only be $90 an hour. A quarter of that value might be lost to lower productivity.

The difference is the worth of a veteran employee to a company.

Worth isn’t an easy figure to calculate. Much depends on the complexity of the business and the uniqueness of its processes.

A company that has strict procedures — common for large conglomerates — will take longer to train a new hire in company processes.

Smaller and more flexible businesses can quickly pivot — hitting their target dates for new employees being integrated and brought up to speed much faster.

The speed with which a business can pivot makes the unique worth of a veteran employee smaller.

One way to calculate your personal worth to your company is to try to estimate how many hours it would take for a replacement to come up to speed. Let’s say you think that someone who replaces you would take 50 hours to move from 80 percent of your productivity — to matching your current output rate.

You take 20 percent of your hourly value multiplied by 50 and this will give you an idea of your worth to the company. In the case of an employee whose skills cost $120 per hour — the replacement cost in this scenario would be $4,800.

The sum of hard cash replacement wouldn’t be the complete picture of the cost-loss to the business.

The worth of an employee to a company extends beyond the financial returns of their work and includes all of the other assets that they bring to a business. The valuation of an employee is also included in their mentoring skills, their personality, management, and creativity contributions.

These “soft skills” might not be assets that are easy to evaluate, but everyone has a few unique soft skills to some degree, contributing to the worth of an employee.

You might not be able to make those calculations yourself — but consider the outcome if you mention to your boss that you feel unhappy at the company.

Your employer would start calculating how much it’s worth to try and get you to stay — or how much trouble they’d save if you were gone.

The employer wouldn’t merely be thinking of how much they pay you because they’d be paying that same amount of money to someone else. The employer will be thinking about the value of your institutional knowledge and the other benefits you bring to the business.

How to prove to your boss the value of your time.

The difference between worth and value is one reason that proving to your boss the value of your time is harder than it sounds. In theory, you should be able just to point out the amount of money each hour your work brings to the business.

Unless you’re exceptionally fast and uniquely productive, your boss will know that they can obtain the same value from a different employee.

To prove to your boss the value of your time, you’ll need to emphasize all of the unique extras that only you bring to each hour of your day. The higher the value of those extra benefits that the company receives from you each hour — the harder you’ll be to replace — and the more valuable you are to the company.

You can look for that additional hourly value in four places:

Institutional knowledge.

We’ve already seen how an awareness of the way a company operates has a value, but demonstrating the importance of that value requires some tact.

You can point out the processes you’ve learned in the time that you’ve been at the company. Mentioning the worth of your knowledge in hourly income might be taken as a criticism of the company’s inefficiency.

The job of a manager is to reduce inefficiencies so it conceivably could be seen as a criticism of your boss.

Rather than talk about the value of your institutional knowledge, you might emphasize the value of the time it would take someone new to learn your skills.

You can point out that time is particularly valuable now. Hours have different values. As time becomes short, it becomes more precious. When a deadline is far away, there are hours and days available for an activity that doesn’t bring a direct revenue correlation — such as training and team bonding.

As the deadline approaches, efficiency has to increase and every minute becomes precious.

Managers want to feel that every minute in the company is precious. Pointing out the number of hours it would take to break in a new employee and comparing that number to the hours available to meet the deadline should help your manager or boss to recognize the value of your time.

Additional professional skills.

A professional will have one main set of skills for which a business — and a client — is willing to pay. But those skills might not be the employees only skills.

A graphic designer might also know a little coding. A coder might know some additional languages or have an eye for Photoshop. A marketing rep might have some good HR connections that make finding new employees relatively easy.

Those skills might not make up the bulk of the employee’s value. The “extra skill” might only be called on five or ten percent of the time they’re at work.

This value-added talent is still available — adding a premium to an employee’s hourly worth.

Imagine that a graphic designer’s value to a company is $120. A programmer’s hourly value at the same company is $200. The designer can do a little programming, but not much. However, when there’s a crunch, she’s able to take some of the pressure off the coders by doing some of the work herself.

If the coding hours have a value of $200 — the time saved by not using a programmer, the company is getting that $200 value for just $120. One way to show your boss the value of your time then is to add up the number of hours each month that you spend doing higher-value work for a lower fee.

Mentoring.

Not all of the value you bring to your company will be from using your professional knowledge.

Some of the advantages of your presence will come from you sharing valuable knowledge with others. Even someone new to an industry brings experience and a unique marketable outlook that can help to improve a company.

Each person brings work habits from their previous company — or new lessons and ideas they’ve picked up at college. That knowledge seeps into the business and improves it.

A new employee learns more than they teach but as they remain in the company, that balance changes.

When new staff arrives, each employee is expected to help bring the new hire up to speed. Each member of the team is needed to show the new individual how the industry works in that particular company.

Often this coaching occurs informally with someone leaning over to lend a hand to a struggling newcomer. With each offer of help, experience grows faster and so does team bonding.

In bigger companies, a supervisor will be expected to train the new hire. Mentoring, whether paid or causally occurring over time also has a value.

To calculate this value — open your calendar and count the number of hours you’ve spent — or will spend — mentoring someone for their job. Maybe you are being promoted and you’re training your replacement.

Count the days and deduct your current salary from the salary you’ll earn when you’re promoted — multiply that amount by the number of mentoring hours.

That number will be the value that your mentoring hours have brought to the company.

For example, supposing part of a fund manager’s job is to train a team member to run his own fund. The fund manager looks at her calendar and finds she’s spent 100 hours mentoring the new would-be fund manager.

The fund manager currently earns $100,000 a year per fund until her replacement takes over the new fund they’re working on. At that time, because of her contribution, knowledge and work, her salary will be raised to $120,000 per year per fund.

When the new, would-be fund manager becomes a fund manager, he’ll begin earning $90,000 per year for this fund. Each hour that the fund manager spends mentoring the new would-be fund manager has added $30,000 divided by 100 — or $300 per year, per account — to that employee’s value.

Team Spirit

The value of professional skills and institutional knowledge, including the time it takes to pass the skills on to others can all be calculated and measured.

There are other ways that an employees’ time benefits a company. One such way is the social effect they have on others.

Colleagues often spend more time with each other than they do with their families. The friendly relationships that form in a workplace can determine whether or not that company is an enjoyable place to work.

Relationships affect staff retention. Team members who work together want to stay together.

Team members who don’t enjoy each other’s company start to look for a different company to work. An employee whose presence in the company makes it an excellent place to stay and work brings value to that company.

Every hour they spend in the firm makes it a better place to work and their presence contributes to the firm’s team spirit. The value of those hours can be measured too.

To calculate the value of your company relationship time, you’ll need to know the turnover rate at the company before you joined.

You’ll want to know the turnover rate since you were hired and gather the information about the cost of onboarding a new employee. The company’s administration department will keep track of the coming and going of employees.

The administration calendar will have a record of each employee’s first day and last day. They should be able to tell you the turnover rates in the months before and since you joined the company.

You should be able to make a reasonable guess at the salaries of your co-workers.

Supposing in the year before you joined the company, the business lost three employees. In the year since you joined the company, just two employees have quit.

When a new employee joins the company it typically takes them three months to move from 80 percent productivity to 100 percent productivity. That’s three months when the employee was generating 20 percent less than the company expected.

If the employee earns $100,000 per year, the lost value over those three months would be about 20 percent of $100,000 divided by twelve months and multiplied by three months — or $25,000.

You wouldn’t be able to claim that all of those savings are a result of your presence in the company, but you could encourage your boss to acknowledge that the company now enjoys a good team spirit.

Remind her that each time a team member leaves and is replaced, it costs the company $25,000 over three months.

How to evaluate time spent closing a lead.

We’ve seen that the value of time is the market value of the product or service created during that time. But not all time at work produces the same product.

Only the lowest level employees get to spend all of their time doing just one thing. The kid who takes orders at the drive-in will spend their entire shift talking through car windows and entering orders into a screen. The company will easily be able to calculate how much it costs to take orders from people in cars.

As workers move up the career ladder, they start to combine different functions.

The supervisor at that drive-in will take her turn in the booth, but she’ll also need to spend time preparing work schedules and making sure the floor is clean. As her day becomes more varied, it becomes harder to separate the value of the different ways in which she spends her time at work.

Those calculations become even harder in professional settings — and harder still for freelancers and the self-employed.

People who run their own businesses will inevitably find themselves doing a wide range of different tasks.

A freelance programmer, for example, might only spend about half their day actually writing lines of code. They’ll also have to take time to stay up to date with their professional literature, read about changes to their chosen languages, and follow developments in coding standards, hardware, and services.

This individual will need to spend time running and testing marketing campaigns, writing bids and pitches, talking to clients and leads, and closing these leads.

The founder and owner will need to know all about the product and take the time to find out how the clients and customers want their final product to work. Each of those featured parts of the business has a separate time value.

Hours spent reading a programming guide or a blog about coding is time not spent writing code for a client.

Nobody is going to pay the programmer for their educational pursuit time. It may be a necessary part of being a professional programmer but it still carries an opportunity cost. Most professional types of work have personal hidden learning costs, which vary from industry to industry.

Professional chefs will need to spend time in markets, buying produce, and ordering new kitchen tools. Personal trainers will need to maintain their own fitness to set an example for their clients. Keynote speakers will need to research, write and practice their speeches — even though they’re only paid for the hour they’ll spend on the stage.

All self-employed people and all freelancers will need to spend time closing leads. They’ll have to break off the paid work that they’re doing to prepare a pitch.

The entrepreneur, startup, new founder, or the self-employed individual still have to estimate quotes, and persuade leads that they’re the best person to complete the job.

Figuring out how much that time cost isn’t complicated. Generally, you’re never going to earn more in an hour than the rate you charge for your professional services.

Therefore, the value of the time spent closing a lead is the number of hours taken to close the lead multiplied by your professional hourly rate:

The number of hours x hourly rate = cost of closing a lead.

The calculation is straightforward, but what you do with that calculation is complex.

Let’s say that you’ve counted the number of hours it’s taken you to prepare a pitch for a lead. You’ve added the time you spent discussing the pitch on the phone with that lead, answering questions, and providing samples.

You’ve thrown in the half-hour it took to draw up the contract, sign it, and send it back to the client. You find that all together you spent two hours turning an inquiry from a lead into a client.

If your normal hourly rate is $120, the cost of closing that lead would be $240. You can’t add that time to an itemized bill. No client is going to pay $240 for a line item that says: “Lead closing.”

Clients would expect you to absorb the cost of your own marketing. So while you might be charging $120 an hour, not all of that money will be for your professional skills.

Some of the funds will cover the time you take to prepare the pitch and close the sale. If the job takes ten hours, then the client will pay $1,200. Your professional skills will cost the client $960. The rest will cover the time it took you to persuade them to give you the job.

You haven’t started working yet, and you’re already earning less than the value of your work. If you can reduce the cost of closing a lead by minimizing the time it takes to procure the work you’ll win many benefits.

First, you’ll be both more competitive and more flexible.

You’ll have more room to offer discounts and more space to negotiate when clients balk at your prices.

Second, you’ll also be able to accept smaller jobs.

If you spend two hours on average closing a lead, then a job that only takes two hours is work you do for free. What you’ll earn working, you’ve already lost in the closing. If you can bring the closing down to half an hour, you’ll be $180 in the black.

Third, you’ll spend more time doing what you love, and less time doing what you must.

Landing a deal is a buzz. Closing is a chore. The people who enjoy it are the people who work in marketing.

How to reduce the time you spend closing a lead.

1. Automate the closing process.

The more information you can take from leads, and the more standardized that information becomes, the easier it will be for you to understand what the lead wants.

Instead of relying on a single field to capture a lead’s inquiry, for example, you could offer a form that requests specific information. An easy automated form with fill-in boxes asking the questions you need to be answered.

The number of pages a website requires, a list of competitors’ sites, and choosing examples of preferred layouts can all be automated.

Having that information before starting to write the pitch proposal would help to reduce the research time required to prepare the bid. You’ll need to strike a balance in your questions and work required from the leads.

Too much demand from leads and they’re likely to pull away before completing their inquiry. Avoid making any of the fields compulsory, but if you can, let your website ask the questions for you. Anything you can automate will save time and shorten the closing process.

2. Cut out timewasters.

The people that pull away from a detailed submission form are unlikely to be ready to close. If they can’t answer the questions on the form — they won’t know what they want yet — and they’ll still be less likely to be in a position to close.

One of the disadvantages of having an easy lead submission process is that you end up spending a lot of time trying to close leads that don’t actually want to buy. Again, you’ll need to strike a balance.

Someone who isn’t ready to buy now might well be prepared to buy after they’ve spoken to you.

You’ll want those people to get in touch with you, but you’ll want to put off those people who are doing little more than market research at the expense of your time. The best way to separate the serious clients is to make them pay in advance at each stage of the process.

The client pays for your time by having to invest time themselves as they complete forms and fill in fields. And they show a commitment to paying for your work by having to make a down payment.

Leads that are unwilling to either pay you for your time or fill out the forms are unlikely to be serious.

Take their contact details and try to sign them up for your newsletter. You’ll want to be their first choice when they are serious and ready to commit. Avoid trying to close leads that can’t be closed yet and you’ll save time and money.

Keep pace with your agenda in each meeting. You’ll have a productive meeting.

The value of meeting time.

The time you spend closing a lead has a cost but at least it has a result. You get a sale out of it — you hope.

There’s another use of time that hits every business and carries a cost. The return on this expenditure is much harder to predict. Businesses have meetings. A business will have production meetings and sales meetings, planning meetings and reviews, board meetings and interviews.

Companies have meetings that last for just a few minutes — and they may have a series of meetings that drag on for days.

Each of those meetings takes up time. They’re hours in which information is shared but products are not created. Ideally, these sessions should ensure that when the meeting ends and the production begins again, those hours are more productive.

Staff should know what they’re doing. A good meeting should result in fewer mistakes and more output. But meetings are still notoriously inefficient.

A meeting can become places where staff members try to impress their bosses or think about what they’re going to have for lunch.

Only a small percentage of the time spent in a meeting actually translates into more productive efforts. Measuring those fruitful moments is difficult.

A business that can tell which minutes of a meeting produce results and which only produce glazed looks will be able to operate at maximum efficiency — and the result will be to have very short meetings.

How do you calculate the value of the meeting time as a whole?

The calculation here is a little more complicated. A meeting doesn’t represent the loss of just one person’s production. It represents the loss of production of everyone in the room.

One way to calculate the cost of a meeting then is to add up the hourly values of each of the participants and multiply them by the length of the meeting.

Let’s take a meeting that lasts ninety minutes attended by a programmer earning $100,000 a year; a graphic designer earning $65,000 a year, and an art director making $120,000 a year. The cost of the meeting is calculated using this formula:

($100,000/1,943 hours) + ($65,000/1,943 hours) + ($120,000/1,943 hours) x 1.5 = $220

To that sum, you’d need to add the price of the croissants and the coffee — but the cost still wouldn’t be entirely accurate.

An art director might spend some of her time producing new designs but the company would assume that she’d spend at least some of her time planning and managing.

Her job would be to sit in meetings, ensuring that the previous week’s work was correctly done and preparing the next week’s tasks. How much time she’d be expected to spend producing and how much time she’d be expected to spend managing would depend on the company.

But if the split were fifty-fifty then opportunity-cost would be about half.

The cost of the meeting would stay the same. Each meeting with those particular participants, for that length of time, would still cost the company $220.

How to reduce the cost of meeting times.

1. Cut the people.

One option is to reduce the number of people at the meeting. Everyone likes to feel part of the decision-making process, and everyone likes to feel that their voice is being heard. But not all of the information being shared in the meeting will be relevant to everyone who attends.

You could invite team members into the meeting to take part in the discussions that affect their work on the project then let them get back to work when the meeting moves on.

You could simply have one of the meeting’s participants fill everyone else in once the meeting is over. That person would need to have two meetings: one to obtain the information, and the other to share it.

But if only a portion of the discussion is being shared, and more than one person is kept at their desk instead of wasting their time in the meeting room you could still end up saving money.

One cost of excluding people from meetings though, is that they start to feel left out. They begin to believe that their voice isn’t being heard and that they have less influence over the direction of the company and its future.

That can start to lower productivity and even push a staff member towards the door.

Before the meeting, ask team members if they have any suggestions or questions that they think should be raised at the meeting. Make a note of their requests and be sure to give them an answer after the meeting has ended.

Employees might not enjoy feeling out of the loop but if they still feel that their voices are being heard, they’ll be grateful for the chance to skip some dull meetings and stick to their work.

2. Shorten the meeting.

An alternative to cutting people from the meeting is to cut time from the meeting. The faster you can move from taking seats to taking out the cups, the lower you have reduced the opportunity cost of the meeting.

The best tool for cutting hours from a meeting is an agenda. When participants know what the meeting will contain, they can prepare. They don’t come to the meeting cold, and they don’t have to think on their feet.

Meetings aren’t meant to be tests of fast thinking. They’re meant to be places where information is exchanged so that ideas and plans can be developed.

Ideally, you want your team to have done their thinking accomplished while they were driving into work or lifting weights in the gym so that they come to the meeting with their thoughts already in order. So that agenda should also contain both time limits and decision points.

Without time limits for each item on the agenda, the meeting can drag on endlessly. Without decision points, it can end without resolution — the biggest waste of time of all.

Each item on the agenda should state how long it will last and what will happen at the end of that discussion period. The agenda could look something like this:

Agenda | ||

| Item | Time allocation | Resolution |

| Sales plan: should we increase this year’s sales target by 10% or 15%? | 15 minutes | New sales target |

| Customer service: how can we increase responsiveness to queries? | 30 minutes | 3 ideas for implementation |

| Training: Who should be invited to the next training session? | 15 minutes | List of trainees |

Note how each of those agenda items is presented as a question? Presenting the format in question form helps to focus thinking.

The first fifteen minutes of a meeting isn’t about the sales plan in general. That time is about the size of the increase in the sales target. Participants have a choice of two options. They can quickly present the reason for their choice before the person calling the meeting makes a decision.

If everyone attending the meeting has a copy of the agenda for a long time before the meeting takes place, they’ll come to the meeting prepared. They’ll have all their arguments and positions in hand, and they’ll be able to lay them out in the timeframe allocated.

One way to ensure that preparation happens is to issue the agenda at the same time that you send out the invitations. Your digital calendar application will let you add attachments.

Write a quick agenda before the meeting begins and attach it to the invitation a good week before the meeting is due to take place. Each minute that you put into preparing for the meeting will save you tens of minutes when the meeting takes place.

How to prove the success of a meeting.

The real question is whether even a shortened meeting is worthwhile. The goal of any meeting is to exchange information and ideas, to come to agreements for action and to assign tasks.

Meetings are often very inefficient ways of doing that. Even with the agenda shared and the presence of people kept to a minimum, meetings can still take a long time to reach their goals. Occasionally there is little choice. Even the best chat communications platforms are inefficient at exchanging information, and they take time too.

What you could achieve in a long series of finger taps, you can often achieve much faster with a quick face-to-face chat. We’ve seen and tested that there are ways to calculate time lost to a meeting.

There are also steps that you can take to minimize those losses before the meeting takes place. Once the meeting has ended, you can look back, measure the cost of that meeting, and weigh that cost against the benefits the meeting brought.

It’s not straightforward and the calculation won’t be entirely accurate. But calculations at any time can still be useful.

To make the calculation, you’ll need to know the productivity of the team affected by the meeting before it takes place, and compare it to the productivity after the meeting has taken place. Each industry and each workplace will need to find its own way to calculate that type of productivity.

One way to make that calculation, for example, might be to count the time lost to revisions or bug-squishing.

Software companies rely on review processes to make sure that the code is working and up to par.

If the average number of bugs found in each production cycle falls from twelve to six, cutting three days from the next production cycle, then the meeting will have done its job.

If, on the other hand, the number of bugs that need to be fixed or the changes that have to be made following a meeting remains the same then you should be asking what improvement the meeting produced. Both of these results can be calculated by comparing productivity over time.

How to show your value on a project.

A meeting is just one of the ways in which time can be stolen from the workday. You should know how much time those meetings are taking, and how much that time is costing you.

In between those periods of lost time you’ll be doing something that should bring real value. You’ll be working on projects. These jobs are what the company pays you for.

The business pays for the time you can put your skills into contributing to the product or service they need and want. That production time — like all time — has a value. There are two ways to work out the value of the time you put into a specific project.

One way is to simply calculate the number of hours you spend on the project and multiply that time by your hourly rate.

If you earn $50 an hour, and you find when you check your calendar that you’ve spent 100 hours on a project, then the cost of your contribution to that project would be $5,000. However, that only shows how much the company paid for your contribution.

It wouldn’t show the value of that contribution. The reason the company pays for your time on a project is that it believes it can sell the results of that time for more money than they paid for it.

The value of the time you put into a project is measured not by the input but by the output.

To measure that value, you’d need to know how much money the project has generated, how much it cost to produce, what portion of those costs were caused by labor — and how much of that labor was contributed by you.

Let’s say, for example, that an artist worked on a mobile video game for a year. The total budget for the game was $1,000,000 and in the year since it was released, it’s generated $5,000,000 in sales and advertising revenue.

Five people worked on the game: an art director, an artist, and three programmers. The art director’s salary is $150,000 a year. The programmers are paid $120,000, and the artist’s salary is $70,000.

The total labor costs for the game can be calculated at $580,000 — of which the artist’s contribution made up about 12 percent. The value of the game, the amount of money that customers have paid to enjoy it, is $5,000,000.

The artist’s contribution is 12 percent of that value, or $600,000. In one year of work, the artist contributed $600,000 worth of value to the project. That represents an hourly rate of a little over $300, a figure worth remembering should the company want to hire the artist on an hourly basis.

Clearly, in practice, these kinds of calculations are rarely that simple.

Employees find it notoriously difficult to estimate the salaries of their co-workers. The success of a product will also be dependent to some extent on the marketing budget and the skills of the influencers and sellers who promote it.

But the principle remains. The more you know about the various costs of the product and the time it took to produce, the better you’ll be able to calculate the value of your own hours.

How your Calendar plays into the value of time.

We’ve seen that the ability to attach agendas to meeting invitations can be a useful way to reduce the cost of time lost in meetings. But that’s just one way in which a calendar can help you to keep track of the value of time.

In fact, calendars are like calculators for tracking and assessing hour-values. Used properly, your calendar will show the number of hours you work. They’ll show what you’re doing during those hours — and they’ll tell how many hours you’re not working and the value of those hours.

Start with the value of your work time.

Digital calendars often let you set the start and end time of your viewing window. It’s unlikely that you’ll be scheduling many events or meetings at three in the morning, so you don’t really need to see it on your calendar. If you work nine to five, Monday to Friday, those are the hours you’ll want to see most clearly on your schedule.

Keeping track of your issues on your Calendar shows how much of your life is dedicated to earning money, and how many hours are dedicated to other things — like living.

Check out your most productive hours — the time when you’ll have your nose to the grindstone and be churning out work. These times dominate your life.

You’ve already seen how to calculate the financial value of each hour you work. Now, when you look at your calendar, you can see how much of your life you’re giving up to reap that financial return.

There’s nothing wrong with putting in plenty of hours at work.

But when you can see that an entire third of the hours on a calendar’s day is spent raising funds to enjoy another third — and the final third is spent sleeping — you can see that the value of work time isn’t just about money.

That big chunk of your calendar represents a giant part of your life. It needs to mean more than cash. Money is important. You need it to pay the bills, to buy food, to pay college loans, and save for your kids’ college fees.

You need that cash so that when you sleep during that last third of the day, you’ll be doing it under a roof and not on a bench in the park. But understand and appreciate that those hours still represent a third of your life.

They should also be delivering satisfaction and enjoyment. They should make you feel that you’re making a difference, even if that difference is only to the customers who enjoy and use your product.

When you reach the end of the last hour in the main window of your calendar, you should feel that you achieved something during those previous hours.

That feeling of accomplishment isn’t something you can measure as easily, but you should try to find a cost-meaning analysis for yourself. You can’t count satisfaction in the same way that you can calculate an hourly rate.

But you can feel it — and you know when you’re getting less satisfaction back for the effort you’re putting in.

You can calculate the financial value of each hour you work, but you should also know how satisfying you find each of those hours and what meaning you can assign to your happiness and satisfaction.

Take a moment to ponder how you feel about your work and what you are bringing to yourself through your efforts.

The Value of Free Time

Around those many hours that you are at work will be a different kind of time — free time. Rather, you may only perceive a small snippet of space that shows the time when you’re not working.

As you look at your calendar — you’ll see the events that aren’t connected to work, and you’re likely to find that you have very little free time.

Digital calendars let you create different schedules for different kinds of events. You can create a “calendar” for your work events but you can also create additional calendars for your sports team’s schedules, for your children’s schools, or for national holidays.

Some calendars will even scan your contacts and automatically create birthday calendars listing everyone you know so that you never forget a gift.

Just as seeing your work calendar will make you aware of how much of your life is dedicated to generating financial value — you will also be able to perceive how well you are doing at accomplishing your other goals in the small amount of time you have left.

The early morning hours on your calendar are likely to be unscheduled because they’re filled with activities that you have to do every day. Your habits of waking-up, breakfast, personal care time for exercise and getting ready for the day, your commute, and so forth.

The evening will be made up of just a few hours that stretch from your commute home to your bedtime, and the eight hours or so that you’re going to spend sleeping.

The revelation that your life is in thirds and that a large chunk of time, out of work, is spent on tasks that you have to do such as laundry, shopping, cleaning, cooking, etc., should have an effect on you.

Hopefully, seeing how much of your week you’re spending at work will prompt you to make sure that those hours are spent doing something you enjoy.

Noting how little free time you have should also inspire you to make sure that your free time is spent well, too. Those are hours that should be filled with meaningful events: outings with your children, courses or lessons, dinners with friends, reading, playing an instrument, learning another language, and time with family.

Again, these aren’t hours on which you can place a dollar value — and that’s fine because time has different kinds of value. Only the time you spend at work carries a price tag. The other hours have a very different value. That doesn’t make them any less precious.

The value of personal time.

The most precious time of all might well be those hours that don’t contain any events at all. Those are the times when you owe nothing to anyone. Your work has no claims on you, your family is doing their own thing, and your friends are busy.

Everyone is entitled to a certain amount of personal time. It’s the time when you get to think and relax and reset your clock. It’s the time in which you find moments of quiet and are able to ditch the stress you’ve picked up during your work hours.

Personal time might make up the smallest number of hours on your calendar but they may well be the most valuable.

The amount of personal time we need varies from person to person. For some people, each hour alone is an hour to treasure. For others, half an hour has them reaching for the phone and looking for a company.

So, while personal time is always valuable, the value that we place on that time will be highly personal. We’ve moved as far from the work hours on which we can place an objective monetary value as it’s possible to travel, and yet still ended up with hours that carry real value.

Time is necessary for reflection and self-improvement

Your time is unique to you, and it can be used in a plethora of ways. While spending time developing one’s career and skills is valuable, it is also valuable to reflect and ponder how you can improve. Without any time to reflect, it can be very easy to get caught up in the day to do habits, and you can seriously limit your potential by doing so. Taking time to reflect on past experience and considering goals and future aspirations can help you identify areas for positive change and overall growth.

Self-reflection and self-improvement may look different for various individuals, but it can lead to greater productivity, leadership, and relationships with others. Many reflect by identifying personal behavioral and cognitive patterns, then making slight tweaks to them to lead to greater efficiency and quality of life. This can lead to greater empathy and better communication between friends, family, and colleagues.

Reflecting can be done through journaling or keeping a gratitude journal. It can take about 10 to 15 minutes and can be a great investment of your time.

Money vs. time.

Throughout this guide, we’ve seen a relationship between money and time. The more valuable work you can squeeze into an hour, the more you’ll earn for each hour of effort.

The more of those hours you work each day, the more you’ll earn in a day, a week, or a month. As you add more work hours to the day, you also lose other valuable time. You lose free time, and you lose personal time. The value of those hours might not be easy –or possible — to calculate but they do have a value.

Money can equal time, but time can be more than equal to money.

Sometimes it creates a conflict when you can’t put a dollar amount on leisure time. You can always calculate the monetary value of hours lost from work.

Freelancers find themselves counting every moment that they take to refresh and reset. How much could they have made in that time? If they need to take a day off sick, they can multiply their hourly rate by the number of hours they lost to learn how much that could cost them.

If they charge $50 an hour, for example, and missed eight hours of work, they’ll have lost $400. They’ll feel that loss when they send out their invoices at the end of the month.

Similarly, if they give up a weekend to cram in more work, they can also count the extra money they’ll have earned. A freelancer who charges $50 an hour and chooses to work for four hours on a Saturday afternoon will add $200 to their income that month.

If they add in those extra working hours a few more times — they’ll have swapped a few weekend hours for a new iPhone.

Any extra money you make is something you can count and see.

But what you are less likely to see is the weakening of a relationship with a spouse or partner left to themselves. You don’t notice the disappointment of your children who would have preferred to have been taken to the park.

You can’t feel the rejuvenation that comes from a walk in the woods if you’ve never taken that stroll and haven’t refreshed yourself with freedom and thought.

The rewards of turning time into money are tangible. The benefits of turning time into a deeper relationship or a valuable memory are much more ephemeral. It’s much easier to lose free time or personal time than it is to lose work time.

Calendars can help safeguard those most important hours by walling you off from others. If you keep your work events within the hours shown on your work calendar, you’ll start to protect your other time.

The protection won’t be absolute. Crises can happen at work, and deadlines can suddenly become tighter. But using a calendar can help to avoid the slippage that makes the time your own. Don’t trade yourself into time exchanged for money.

Conclusion — The value of time.

We all have the same amount of time. We all have the same number of hours in a day, the same number of days in a week, and the same number of weeks in a year. Time is the great equalizer. The amount of money that we earn in that time, though, will vary tremendously.

We’ve seen how that value of your time is influenced by skill, by demand, and by your productivity.

We’ve also seen that value is influenced by knowledge. The more you know about the value of your time, the more you’ll treasure it and the less you’ll waste it.

Updated January 2023

John Rampton

John’s goal in life is to make people’s lives much more productive. Upping productivity allows us to spend more time doing the things we enjoy most. John was recently recognized by Entrepreneur Magazine as being one of the top marketers in the World. John is co-founder and CEO of Calendar.